Virtual Exhibition Guide

The Riddle

David Breashears is an accomplished mountaineer, photographer, and filmmaker. He is also the founder and Executive Director of GlacierWorks, a non-profit organization that uses art, science, and adventure to raise public awareness about the consequences of climate change in the Greater Himalayan Region. Since 1978 he has combined his skills in climbing and filmmaking to complete more than forty film projects. He co-directed and produced the first IMAX film shot on Mount Everest, and reached the summit of Everest for the fifth time in 2004 when shooting his film Storm Over Everest. Website

Hear From The Photographer

Jimmy Chin is a photographer, filmmaker, and mountain sports athlete known for his ability to capture extraordinary imagery while climbing and skiing in high-risk environments. With his wife Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, he directed the filmsMeru (2015), which won the coveted Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival, and Free Solo (2018), which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. As a mountaineer, he has both summited and skied down from Everest. Chin has garnered numerous photography awards from PDN, Communication Arts, the American Society of Magazine Editors, and others. Chin’s photos have appeared on the cover of National Geographic and The New York Times Magazine, among others. His most recent film is The Rescue (2020), which chronicles the 2018 rescue of a youth football team from Tham Luang cave in Thailand. Website | Instagram | Twitter

Jimmy Chin is a photographer, filmmaker, and mountain sports athlete known for his ability to capture extraordinary imagery while climbing and skiing in high-risk environments. With his wife Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, he directed the filmsMeru (2015), which won the coveted Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival, and Free Solo (2018), which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. As a mountaineer, he has both summited and skied down from Everest. Chin has garnered numerous photography awards from PDN, Communication Arts, the American Society of Magazine Editors, and others. Chin’s photos have appeared on the cover of National Geographic and The New York Times Magazine, among others. His most recent film is The Rescue (2020), which chronicles the 2018 rescue of a youth football team from Tham Luang cave in Thailand. Website | Instagram | Twitter

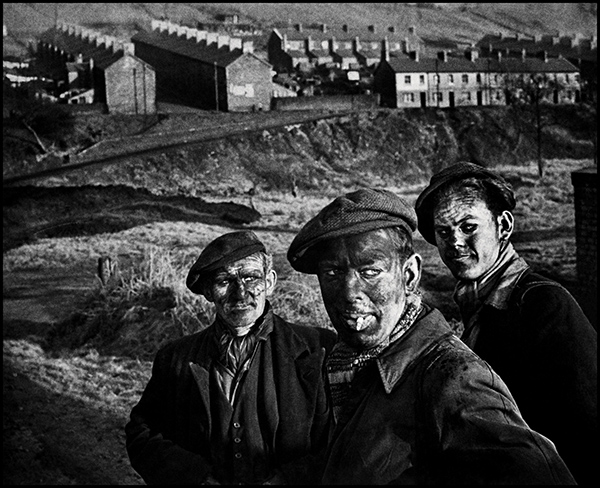

Bruce Davidson began taking photographs at the age of ten in Oak Park, Illinois. He became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1958 and created such seminal bodies of work as The Dwarf, Brooklyn Gang, and Freedom Rides. In 1963 the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented his early work in a solo show. His work witnessing the dire social conditions on one block in East Harlem was published in 1970 under the title East 100th Street. In 1980, he captured the vitality of the New York Metro’s underworld that was later published in a book, Subway. His awards include the Lucie Award for Outstanding Achievement in Documentary Photography in 2004 and a Gold Medal Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Arts Club in 2007.

Bruce Davidson began taking photographs at the age of ten in Oak Park, Illinois. He became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1958 and created such seminal bodies of work as The Dwarf, Brooklyn Gang, and Freedom Rides. In 1963 the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented his early work in a solo show. His work witnessing the dire social conditions on one block in East Harlem was published in 1970 under the title East 100th Street. In 1980, he captured the vitality of the New York Metro’s underworld that was later published in a book, Subway. His awards include the Lucie Award for Outstanding Achievement in Documentary Photography in 2004 and a Gold Medal Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Arts Club in 2007.

Born in Yongcheng, Henan province in 1962. Yu Haibo graduated from Wuhan University as a photography major. Yu has won many national and provincial photographic awards. Since 2006, his project Dafen Oil Painting Village has been widely exhibited in China, Amsterdam, Paris, Zurich and Lodz, Poland, and collected by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He is now the chief news photographer of the Shenzhen Economic Daily. He is also the Director of the Shenzhen Professional Photography Association.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

“I have tried to let the truth be my prejudice. It has taken much sweat. It has been worth it.”

–W. Eugene Smith

William Eugene Smith was born in 1918 in Wichita, Kansas. He worked as a war correspondent for Flying magazine (1943-1944), and a year later for Life. He followed the island-hopping American offensive against Japan, and suffered severe injuries. Smith worked for Life again between 1947 and 1955, before resigning to join Magnum Photos. He was fanatically dedicated to his mission as a photographer, and once said, “I’ve never made any picture, good or bad, without paying for it in emotional turmoil.” His legacy lives on through the W. Eugene Smith Fund to promote “humanistic photography,” founded in 1980, which awards photographers for exceptional accomplishments in the field.

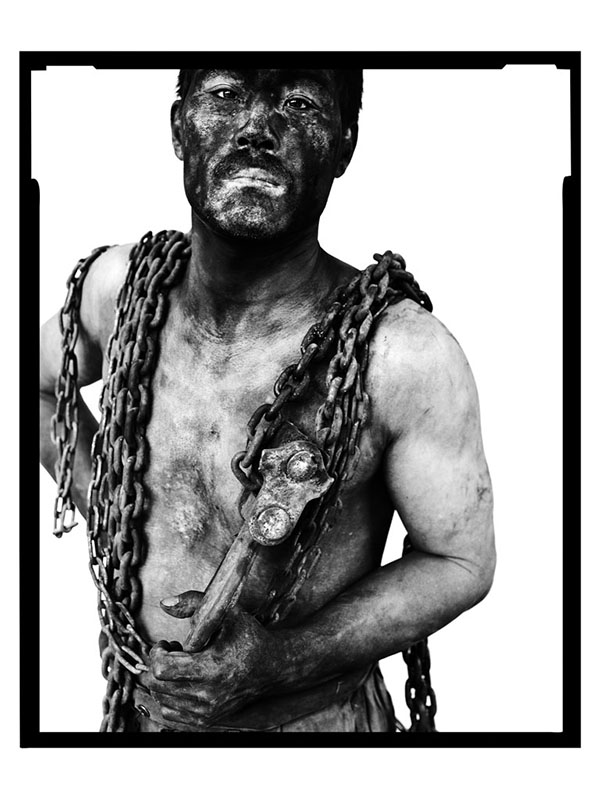

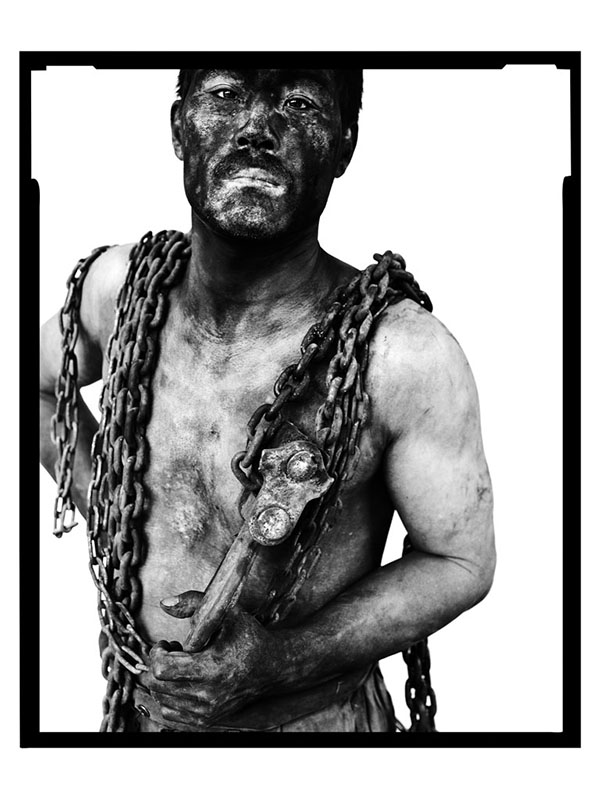

Born in Dongming county, Shandong province in 1979, Song Chao began working as a miner in Shandong’s Yankuang Group in 1997. He began to take photographs of his coworkers in 2001, at first using a homemade studio at the entrance of the mine and balancing his photographic work with 12-hour mining shifts. His projects since then have included Miners I and II, Miner’s Families, Coal Mine Community, and two projects on migration, Migrant Workers and Hold. All feature his signature style of stark black-and-white portraiture with a whited-out background. In 2002, Song received the Chinese National Photography Award. He now lives in Beijing, where he graduated from Beijing Film Academy in 2009.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

“Photography is an empathy towards the world.”

–Lewis Hine

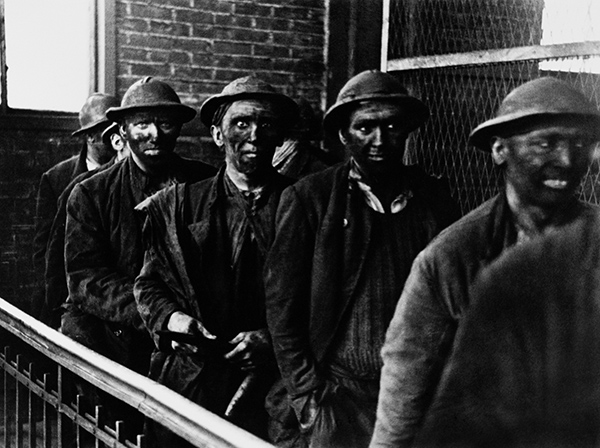

Lewis Hine was an American teacher, sociologist, and muckraking photographer whose photographs helped expose and end child labor in the United States. Born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Hine took up photography in 1904 to document immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. After attending the Columbia University School of Social Work, Hine began photographing for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) in 1907. He traveled from Maine to Texas documenting children working in factories, mines, mills, farms, and street trades. Declaring that he “wanted to show things that had to be corrected,” Hine was one of the earliest photographers to use the photograph as a documentary tool. In 1936 Hine was appointed head photographer for the National Research Project of the Works Projects Administration. He died in 1940.

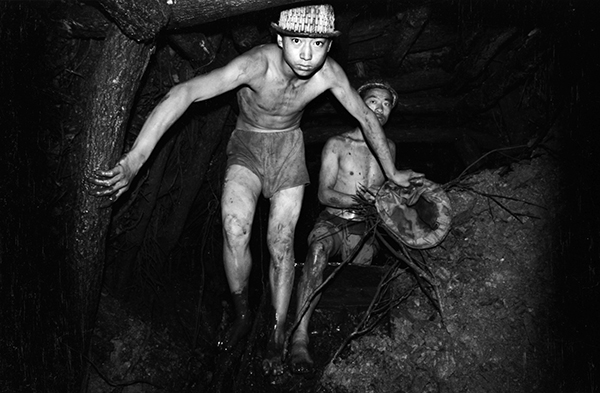

Born in Kunming, Yunnan province in 1954, Geng Yunsheng started to learn photography in 1990. He has been invited to international photo festivals in Pingyao, Lianzhou, Shenyang, and Taiwan. Over many trips to the Wumeng region, he documented coal miners at work and at leisure as well as the environment in which they lived and the abysmal conditions of the mines themselves. The project that resulted, Wumeng Miners, has won him several national photographic awards, and has been widely exhibited in Germany, France, and the United States. A book with the same title was published in 2010.

Hear from the Photographer

Interview from 2015

Q: So…I guess, you have always been saying that the closing of the mines was affecting the community, and you’re saying that’s what’s happening now?

A: 有影响。当地冬季气候寒冷,居民需烧煤取暖,部分小煤窑是村民自给自足生活所需的煤炭,如做饭、烤火。政府关闭之后不允许开采,需另行购买,但他们的经济收入低,负担不起,这对当地老百姓的家庭生活有影响。我曾与煤炭老板交流,如果禁止开采,居民们会转而砍伐树木这另一稀缺资源,将造成更严重的生态环境破坏。

A: The answer must be yes. Because of the cold weather in winter, local people were used to burning coal for heat. Some small-sized coal mines built by the locals provided for their cooking and heating needs. When the mine got closed they had no other way to access coal except buying it, which they could barely afford due to their low income. As I told someone in charge of the coal mines, if mining is banned the locals may turn to cutting down trees, another scarce resource. And this may do greater harm to the environment.

Q: How do local people react when you show your book? Are they surprised at the photos?

A: 当地人还没有机会看到我后来的作品,除了我之前寄回去的合影。当我第二次去煤窑的时候已经找不到他们了。他们不是工人而是种地的农民,人口流动性大,觉得挖煤条件艰苦而且危险所以不做了。

A: I didn’t have a chance to show them my works except the pictures we took together, because when I went back there I couldn’t find them. Local people are not just miners but also farmers. They are moving here and there. Once they realized coal mining is not just tough work but also dangerous, they quit.

Q: What about people in the city unfamiliar with the coal mine? What’s their reaction?

A: 看到展览照片大家都很震惊,不敢相信这样的画面会发生在我们国家,如今社会。包括著名摄影家,北京王文楠(音)先生,观展后感觉“心被撕裂了”。

A: Many citizens are shocked by my exhibition. They just could not believe that kind of scene may occur in our country in today’s society. The famous photographer Wang Wennan from Beijing said after viewing the exhibition that he felt that his “heart was torn apart”.

Q: One of the photos shows a small child in the coal mine, it looks like a very young boy. Can you tell us about that photo?

A: 在拍摄的时候我还没接触过他。当我看到画面的一瞬间,他躺在那儿很打动我(哽咽…)当我准备按下快门的时候,看见他很无助地躺在那儿。我差点不能按下跨门,但还是坚持将他拍了下来。我后来得知他们两兄弟,一个13岁,一个11岁。我的书中还有另一张照片,他们一直很感动我。

A: Not until I finished my work did I get to know the boy. The moment I met him he was lying in front of me, choked. I was so affected I almost couldn’t press the shutter, because he looked so helpless. But I insisted on shooting him. I later learned there were two brothers, one is 13 while the other is 11. There is another photo of them in my book, and it continually touches my heart.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

“We are only trying to tell a story. Let the 17th-century painters worry about the effects. We’ve got to tell it now, let the news in, show the hungry face, the broken land, anything so that those who are comfortable may be moved a little.”

–David Seymour

“Chim picked up his camera the way a doctor takes his stethoscope out of his bag, applying his diagnosis to the condition of the heart.”

–Henri Cartier-Bresson

David Szymin was born in 1911 in Warsaw. After studying at the Sorbonne in the 1930s, Szymin stayed on in Paris. From 1936 to 1938 he photographed the Spanish Civil War. On the outbreak of World War II he moved to New York, where he adopted the name David Seymour. To his friends, however, he was always known by his nickname, “Chim.” In 1947, along with Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, George Rodger, and William Vandivert, he founded Magnum Photos. In 1956, when traveling near the Suez Canal to cover a prisoner exchange, he was killed by Egyptian gunfire.

David Szymin was born in 1911 in Warsaw. After studying at the Sorbonne in the 1930s, Szymin stayed on in Paris. From 1936 to 1938 he photographed the Spanish Civil War. On the outbreak of World War II he moved to New York, where he adopted the name David Seymour. To his friends, however, he was always known by his nickname, “Chim.” In 1947, along with Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, George Rodger, and William Vandivert, he founded Magnum Photos. In 1956, when traveling near the Suez Canal to cover a prisoner exchange, he was killed by Egyptian gunfire.

Coal Miners

Prints I

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

Born in the UK of Welsh descent, David Hurn is a self-taught photographer. He gained his reputation with his reportage of the 1956 Hungarian revolution. Hurn became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1967. In 1973 he set up the famous School of Documentary Photography in Newport, Wales. He recently collaborated on a very successful textbook with Professor Bill Jay, On Being a Photographer. However, it is his book Wales: Land of My Father that truly reflects Hurn’s style and creative impetus. Instagram

“No tricks are necessary….You don’t have to pose your camera. The pictures are there, and you just take them. The truth is the best, the best propaganda.”

–Robert Capa, interview with New York World-Telegram, 1937

Widely considered one of the greatest war photographers of all time, Robert Capa was born Andre Friedmann to Jewish parents in Budapest in 1913. Settling in Paris in 1933, he invented the persona of “famous” American photographer Robert Capa and began to sell his prints under that name. Capa’s coverage of the Spanish Civil War won him international fame and his picture of a loyalist soldier who had just been fatally wounded became a powerful symbol of war. Capa went on to extensively cover World War II, including the landing at Omaha Beach during the invasion of Normandy. In 1947, he co-founded Magnum Photos. Capa died when he stepped on a landmine while photographing for Life in Indochina in 1954. He was 40 years old.

Widely considered one of the greatest war photographers of all time, Robert Capa was born Andre Friedmann to Jewish parents in Budapest in 1913. Settling in Paris in 1933, he invented the persona of “famous” American photographer Robert Capa and began to sell his prints under that name. Capa’s coverage of the Spanish Civil War won him international fame and his picture of a loyalist soldier who had just been fatally wounded became a powerful symbol of war. Capa went on to extensively cover World War II, including the landing at Omaha Beach during the invasion of Normandy. In 1947, he co-founded Magnum Photos. Capa died when he stepped on a landmine while photographing for Life in Indochina in 1954. He was 40 years old.

Born in Pingdingshan, Henan province in 1963, Yang Junpo worked for manufacturing and mining companies in Henan before turning to photography in 1978. He began doing street photography in the city of Shenzhen in 1994. Yang’s style is to merely document, rather than artistically express, daily life in the urban environment. His project Small Coal Mines, which he started in 1996, takes a similar approach to photographing coal miners at work. Yang has now been a commercial photographer for the Shenzhen Authentic Vision Company since 1998, and his work has been shown in major photo festivals in China. He lives and works in Shenzhen.

Born in Pingdingshan, Henan province in 1963, Yang Junpo worked for manufacturing and mining companies in Henan before turning to photography in 1978. He began doing street photography in the city of Shenzhen in 1994. Yang’s style is to merely document, rather than artistically express, daily life in the urban environment. His project Small Coal Mines, which he started in 1996, takes a similar approach to photographing coal miners at work. Yang has now been a commercial photographer for the Shenzhen Authentic Vision Company since 1998, and his work has been shown in major photo festivals in China. He lives and works in Shenzhen.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

Prints II

Robert Wallis started his career in San Francisco photographing subjects ranging from Mexican American gang culture to the gay clubbing scene at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic. Now London-based, He has specialized in photographing countries undergoing rapid economic and social change. He is particularly concerned with the environmental impact of the global race to achieve Western standards of living. He has documented this in stories such as “The Dark Side of the Boom,” where “development” in India means one thing for a growing urban middle class and quite another for those living on top of minerals needed to fuel the boom. This work culminated in a major multimedia exhibition at London’s School of Oriental and African studies in 2011. Website | Facebook

Robert Wallis started his career in San Francisco photographing subjects ranging from Mexican American gang culture to the gay clubbing scene at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic. Now London-based, He has specialized in photographing countries undergoing rapid economic and social change. He is particularly concerned with the environmental impact of the global race to achieve Western standards of living. He has documented this in stories such as “The Dark Side of the Boom,” where “development” in India means one thing for a growing urban middle class and quite another for those living on top of minerals needed to fuel the boom. This work culminated in a major multimedia exhibition at London’s School of Oriental and African studies in 2011. Website | Facebook

Stuart Franklin was born in Britain in 1956. During the 1980s, he worked as a correspondent for Sygma Agence Presse in Paris before joining Magnum Photos in 1985. His documentary photography has taken him to Central and South America, China, Southeast Asia, and Europe. He took several of the famous “Tank Man” photos during the 1989 Tiananmen protests in Beijing. Since 2004 he has focused on long-term projects concerned primarily with man and the environment. Franklin is currently working on a long-term project on Europe’s changing landscape, focusing in particular on the climate and on patterns of transformation. Website | Twitter | Instagram

Born in Jining, Shandong province, in 1968, Wang now is the Business Director of Shandong Pictorial magazine. He has been recognized as one of the top ten photographers in the province. He is a member of the China Photographers’ Association, as well as the Deputy Secretary of Shandong Youth Photographers’ Association. He has been awarded prizes in several dozen national and provincial photographic competitions and has had his work published in numerous print media outlets. He has organized and curated national-level photography projects including the Photographer’s Vision on Prison and Photojournalists’ Focus on Yunkuang.

Hear from the Photographer

Interview from 2015

因为我曾经在煤矿上工作过11年,我对煤矿特别了解。2001年我调任山东画报社做记者,对煤矿又有了新一层的了解。我经常去山东的各种煤矿,大大小小都去过。和别人采访的地方不同,我去的都是山东的国营大型煤矿,我认为是代表中国现阶段最现代化的煤矿,例如兖矿集团,它在1999年之前曾经是中国第一大煤矿。

Because I have worked in a coal mine for 11 years, so I know a lot about it. In 2001, I was transferred to Shandong Pictorial. There I started my career as a journalist. I got the chance to visit all kinds of coal mines in Shandong, with all scales, especially those state-owned large scale coal mines, which I think represent the most advanced coal mining production in China. For example, Shandong Yankuang Group used to be the biggest coal mine in China before 1999.

Q:您在矿上的时候主要从事什么工作?

Q: What type of work were you doing at the coal mine?

A: 我的工作是教师,兼任宣传,包括上煤矿拍照片等,是在煤矿的学校里工作。

A: Actually I worked as a teacher in our coal mine. I also did communication and publicity for the coal mine, including shooting photos.

A:当时我虽然是老师,但是大学期间我就喜欢摄影,拍摄了许多反映中国社会问题的报道,在《人民日报》等中国很多大媒体上都发表过。所以2001年我得以转到山东画报社,当专职记者。

A: Though my first job is teaching, I started photography when I was in college. I have shoot many photos reflecting social issues in China, and these works finally got published in influential media in China, such as People’s Daily. So in 2001 I got this chance to make a career shift to be a real journalist.

Q:您所见到煤矿的变化是什么?您现在还会回煤矿拍摄吗?

Q: What sort of change did you see in the coal mines? Do you still go back to photograph them now?

A:因为我和这些煤矿的关系特别好,前一段时间我还跟着兖矿集团去陕西拍摄他们井下作业。我上煤矿采访时工作,工作之余我会拍摄一些煤矿工作中我感兴趣的照片。

A: Because I have a very good relationship with these coal mines, I always go back. Recently I went with Yankuang Group to Shaanxi, shooting photos of their work underground. My job was to do news coverage of coal mines, but I also took photos which I think interest me and to go with the coverage.

Q:那这是非常不错的副产品。

Q: It’s a very good byproduct.

A:因为我和这些煤矿的人都是朋友,所以我可以任意去我想去的地方拍摄,包括井下,而通常一般的摄影师没法去井下拍摄。

A: Because I’m friends with them. So I went anywhere I wanted in the coal mine, even down in the coal pit, which is usually closed to other photographers.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

Born in 1955 in Henan province’s Baofeng county, Niu has been a freelance photographer since the 1980s and began to photograph coal mines in 1987. He chose coal as his subject because of its centrality in daily life in his home city of Pingdingshan. He has also worked as an official in the Pingdingshan City Bureau of Public Security since 1980, due to the difficulty of making a living as a full-time photographer in China. His major works include Career Behind Bars, Martial Arts, In Dreams, Garden of Hundred Flowers, Small Coal Mines, and Exercises. Niu’s work is in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and has been published in Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Thomas Hoepker studied art history and archeology, then worked as a photographer for Münchner Illustrierte and Kristall between 1960 and 1963, reporting from all over the world. He joined Stern magazine as a photo-reporter in 1964. Specializing in reportage and stylish color features, he received the prestigious Kulturpreis of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie in 1968. Among his iconic photographs are a group of people talking on the Brooklyn waterfront on 9/11 and Mohammed Ali extending his fist in front of the Chicago skyline. Today Hoepker lives in New York. A retrospective exhibition, showing 230 images from fifty years of work, toured Germany and other parts of Europe in 2007.

Thomas Hoepker studied art history and archeology, then worked as a photographer for Münchner Illustrierte and Kristall between 1960 and 1963, reporting from all over the world. He joined Stern magazine as a photo-reporter in 1964. Specializing in reportage and stylish color features, he received the prestigious Kulturpreis of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie in 1968. Among his iconic photographs are a group of people talking on the Brooklyn waterfront on 9/11 and Mohammed Ali extending his fist in front of the Chicago skyline. Today Hoepker lives in New York. A retrospective exhibition, showing 230 images from fifty years of work, toured Germany and other parts of Europe in 2007.

Cube I

“Photography is an empathy towards the world.”

–Lewis Hine

Lewis Hine was an American teacher, sociologist, and muckraking photographer whose photographs helped expose and end child labor in the United States. Born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Hine took up photography in 1904 to document immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. After attending the Columbia University School of Social Work, Hine began photographing for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) in 1907. He traveled from Maine to Texas documenting children working in factories, mines, mills, farms, and street trades. Declaring that he “wanted to show things that had to be corrected,” Hine was one of the earliest photographers to use the photograph as a documentary tool. In 1936 Hine was appointed head photographer for the National Research Project of the Works Projects Administration. He died in 1940.

Born in Dongming county, Shandong province in 1979, Song Chao began working as a miner in Shandong’s Yankuang Group in 1997. He began to take photographs of his coworkers in 2001, at first using a homemade studio at the entrance of the mine and balancing his photographic work with 12-hour mining shifts. His projects since then have included Miners I and II, Miner’s Families, Coal Mine Community, and two projects on migration, Migrant Workers and Hold. All feature his signature style of stark black-and-white portraiture with a whited-out background. In 2002, Song received the Chinese National Photography Award. He now lives in Beijing, where he graduated from Beijing Film Academy in 2009.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

Gleb Kosorukov was born in Chelyabinsk-70, a secret city and nuclear research center in Urals, Russia. He studied at the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute where he graduated in 1990 with a diploma in experimental nuclear physics. Starting in 1992 he worked as a freelance photographer for publications like The New York Times, The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times Magazine, Time, Newsweek, and Stern in Russia. Kosorukov began working on art and documentary projects in 1998 and has regularly shown at exhibitions in Russia and abroad in cities like Reykjavik, Frankfurt, Dusseldorf, and Paris.

Gleb Kosorukov was born in Chelyabinsk-70, a secret city and nuclear research center in Urals, Russia. He studied at the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute where he graduated in 1990 with a diploma in experimental nuclear physics. Starting in 1992 he worked as a freelance photographer for publications like The New York Times, The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times Magazine, Time, Newsweek, and Stern in Russia. Kosorukov began working on art and documentary projects in 1998 and has regularly shown at exhibitions in Russia and abroad in cities like Reykjavik, Frankfurt, Dusseldorf, and Paris.

Born in Yongcheng, Henan province in 1962. Yu Haibo graduated from Wuhan University as a photography major. Yu has won many national and provincial photographic awards. Since 2006, his project Dafen Oil Painting Village has been widely exhibited in China, Amsterdam, Paris, Zurich and Lodz, Poland, and collected by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He is now the chief news photographer of the Shenzhen Economic Daily. He is also the Director of the Shenzhen Professional Photography Association.

Anna Filipova is a photojournalist and a researcher based in Paris. She has been working for The New York Times International Edition, The International Herald Tribune, and Reuters News Agency and has been published in CNN, Washington Post, The Telegraph, Dazed & Confused, and The Guardian, amongst others. For the past few years, she has been focusing on the Arctic region, where she explores environmental and social topics in remote and inaccessible areas. She has a MA from the Royal College of Art in London. Most recently, the mayor of Paris and President of C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group selected Filipova as one of the climate heroines representing the city of Paris. Website | Twitter | Instagram

Anna Filipova is a photojournalist and a researcher based in Paris. She has been working for The New York Times International Edition, The International Herald Tribune, and Reuters News Agency and has been published in CNN, Washington Post, The Telegraph, Dazed & Confused, and The Guardian, amongst others. For the past few years, she has been focusing on the Arctic region, where she explores environmental and social topics in remote and inaccessible areas. She has a MA from the Royal College of Art in London. Most recently, the mayor of Paris and President of C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group selected Filipova as one of the climate heroines representing the city of Paris. Website | Twitter | Instagram

Hear From the Photographer

I live in the Arctic, where I cover environmental and science stories. I always try to reveal unseen stories, and to create a sense of wonder. I hope my work will help to strengthen the presence of women in science and environmental photojournalism where previously the feminine perspective has been underrepresented.

Cube II

“A documentary must be cinematic, a dramatization of daily life. It must make people think and in an extreme militant sense, it can agitate. In form, it can go from newsreel to fiction. Authenticity, after all, isn’t necessarily truth. Fiction can be truer.”

–Joris Ivens, 1988 Los Angeles Times interview

“Similarly, the newsreel offers everyone the opportunity to rise from passer-by to movie extra. In this way any man might even find himself part of a work of art, as witness Vertofl’s Three Songs about Lenin or Ivens’ Borinage. Any man today can lay claim to being filmed.”

–Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”

Joris Ivens, born Georg Henri Anton Ivens in 1898 in the Netherlands, was a Dutch filmmaker who explored leftist social and political concerns. Ivens received acclaim for two of his early films, The Bridge (1928) and Rain (1929). His successes resulted in an invitation to lecture in the Soviet Union, where he made Song of Heroes (1932). His most famous film was The Spanish Earth (1937), an anti-Franco report on the Spanish Civil War written by Ernest Hemingway and Jon Dos Passos and narrated by Orson Welles. His film The Power and the Land (1940) documents the New Deal’s rural electrification program. He died in Paris in 1989.

Joris Ivens, born Georg Henri Anton Ivens in 1898 in the Netherlands, was a Dutch filmmaker who explored leftist social and political concerns. Ivens received acclaim for two of his early films, The Bridge (1928) and Rain (1929). His successes resulted in an invitation to lecture in the Soviet Union, where he made Song of Heroes (1932). His most famous film was The Spanish Earth (1937), an anti-Franco report on the Spanish Civil War written by Ernest Hemingway and Jon Dos Passos and narrated by Orson Welles. His film The Power and the Land (1940) documents the New Deal’s rural electrification program. He died in Paris in 1989.

“The camera that lacks respect for human beings distorts the truth.”

–Henri Storck, interview by Andrée Tournès, 1988

Henri Storck was a filmmaker and an important member of the Belgian avant-garde in the 1920s and ‘30s. He was born in 1907 in Ostend, Belgium. As a young man, he was influenced by surrealism and was associated with René Magritte, André Malraux, Louis Aragon, and others. His early films were silent “ethnographic” tableaus depicting everyday life in his home region. Storck was best known for his social documentaries, most notably Misery in Borinage, which he made together with Joris Ivens. During World War II he filmed the sociological documentary Farmers’ Symphony. Storck made nearly 100 films. He died in 1999.

Henri Storck was a filmmaker and an important member of the Belgian avant-garde in the 1920s and ‘30s. He was born in 1907 in Ostend, Belgium. As a young man, he was influenced by surrealism and was associated with René Magritte, André Malraux, Louis Aragon, and others. His early films were silent “ethnographic” tableaus depicting everyday life in his home region. Storck was best known for his social documentaries, most notably Misery in Borinage, which he made together with Joris Ivens. During World War II he filmed the sociological documentary Farmers’ Symphony. Storck made nearly 100 films. He died in 1999.

Born in 1955 in Henan province’s Baofeng county, Niu has been a freelance photographer since the 1980s and began to photograph coal mines in 1987. He chose coal as his subject because of its centrality in daily life in his home city of Pingdingshan. He has also worked as an official in the Pingdingshan City Bureau of Public Security since 1980, due to the difficulty of making a living as a full-time photographer in China. His major works include Career Behind Bars, Martial Arts, In Dreams, Garden of Hundred Flowers, Small Coal Mines, and Exercises. Niu’s work is in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and has been published in Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

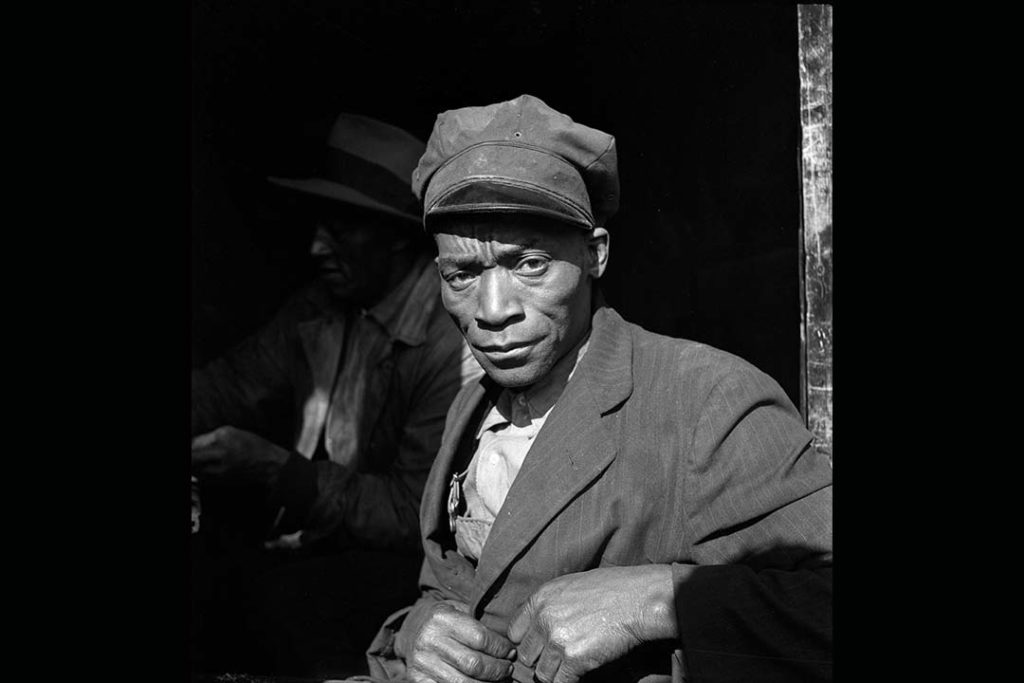

“I chose my camera as a weapon against all the things I dislike about America—poverty, racism, discrimination.”

–Gordon Parks, A Choice of Weapons, 1967

Gordon Parks was a dedicated humanitarian who broke the color line to become one of the most celebrated American photographers of the 20th century. Born in Kansas in 1912, Parks experienced first-hand deep American racism and poverty. He taught himself photography as a tool for documenting the social conditions he saw around him. Despite his lack of training, Parks became a photographer for New Deal-era government agencies and traveled the country documenting race relations and social inequality. He would continue to photograph American society, protest movements, fashion, and urban life in a long career as a Life magazine staffer and freelance photojournalist. A renaissance man, Parks was also a pioneering blaxploitation filmmaker, writer, painter, and composer.

Gordon Parks was a dedicated humanitarian who broke the color line to become one of the most celebrated American photographers of the 20th century. Born in Kansas in 1912, Parks experienced first-hand deep American racism and poverty. He taught himself photography as a tool for documenting the social conditions he saw around him. Despite his lack of training, Parks became a photographer for New Deal-era government agencies and traveled the country documenting race relations and social inequality. He would continue to photograph American society, protest movements, fashion, and urban life in a long career as a Life magazine staffer and freelance photojournalist. A renaissance man, Parks was also a pioneering blaxploitation filmmaker, writer, painter, and composer.

Barbara Kopple produced and directed Harlan County, USA and American Dream, both winners of the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. In 1991, Harlan County, USA was named to the National Film Registry by the Librarian of Congress and designated an American Film Classic. The Criterion Collection released a DVD of Harlan County, USA in 2006, and it is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel and HBO/MAX. Kopple is also a nine-time Emmy-nominated filmmaker. Heading up Cabin Creek Films in New York City, she is a director and producer of documentaries, scripted films, episodic television, and commercials. She is a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, the Director’s Guild of America, New York Women in Film and Television’s Honorary Board, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, and actively participates in organizations that address social issues and support independent filmmaking. Website | Twitter

Barbara Kopple produced and directed Harlan County, USA and American Dream, both winners of the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. In 1991, Harlan County, USA was named to the National Film Registry by the Librarian of Congress and designated an American Film Classic. The Criterion Collection released a DVD of Harlan County, USA in 2006, and it is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel and HBO/MAX. Kopple is also a nine-time Emmy-nominated filmmaker. Heading up Cabin Creek Films in New York City, she is a director and producer of documentaries, scripted films, episodic television, and commercials. She is a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, the Director’s Guild of America, New York Women in Film and Television’s Honorary Board, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, and actively participates in organizations that address social issues and support independent filmmaking. Website | Twitter

Cube III

Born in Kaifeng, Henan province in 1966, Wu Qi graduated from the Art Department of Suzhou University in 1990. Wu currently does photography and works in commercial printing design. His project The day does not know the darkness of the night has been exhibited at the Pingyao International Photography Festival in Shanxi Province and the Paris Photography Biennial. Wu’s Heavy Dust series of grainy nighttime depictions of coal mines is intended to present the mines as wartime or horror film scenes. He is the founder of the Golden Apple Design Company. Website | Instagram

Born in Kaifeng, Henan province in 1966, Wu Qi graduated from the Art Department of Suzhou University in 1990. Wu currently does photography and works in commercial printing design. His project The day does not know the darkness of the night has been exhibited at the Pingyao International Photography Festival in Shanxi Province and the Paris Photography Biennial. Wu’s Heavy Dust series of grainy nighttime depictions of coal mines is intended to present the mines as wartime or horror film scenes. He is the founder of the Golden Apple Design Company. Website | Instagram

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

Ian Teh is a documentary photographer who has often focussed on China. His Dark Clouds project depicts daily working life in China’s northeastern rust belt. The photographs lay bear the contrast between the vast desolation of the landscape and the humans who work within it, and, by extension, the larger population who benefits from the economic activity produced there. Teh has published three monographs, Undercurrents (2008), Traces (2011), and Confluence (2014). In 2018 he was awarded a travel grant from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting and presented his work on climate change at the prestigious 2018 National Geographic Photography Seminar. He is also the recipient of the International Photoreporter Grant (2016), the Abigail Cohen Fellowship in Documentary Photography (2014), and the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund (2011). In 2013 he was elected by the Open Society Foundations to exhibit in New York at the Moving Walls exhibition. Website | Instagram | Facebook

Ian Teh is a documentary photographer who has often focussed on China. His Dark Clouds project depicts daily working life in China’s northeastern rust belt. The photographs lay bear the contrast between the vast desolation of the landscape and the humans who work within it, and, by extension, the larger population who benefits from the economic activity produced there. Teh has published three monographs, Undercurrents (2008), Traces (2011), and Confluence (2014). In 2018 he was awarded a travel grant from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting and presented his work on climate change at the prestigious 2018 National Geographic Photography Seminar. He is also the recipient of the International Photoreporter Grant (2016), the Abigail Cohen Fellowship in Documentary Photography (2014), and the Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund (2011). In 2013 he was elected by the Open Society Foundations to exhibit in New York at the Moving Walls exhibition. Website | Instagram | Facebook

Born in Kunming, Yunnan province in 1954, Geng Yunsheng started to learn photography in 1990. Geng has been invited to many international photo festivals in Pingyao, Lianzhou, Shenyang and Taiwan. Over many trips to Wumeng region, he documented coal miners at work and at leisure as well as the environment in which they lived and the abysmal conditions of the mines themselves. The project that resulted, Wumeng Miners has won him several national photographic awards, and has been widely exhibited in Germany, France and the U.S. A book with the same title was published in 2010.

Born in Kunming, Yunnan province in 1954, Geng Yunsheng started to learn photography in 1990. Geng has been invited to many international photo festivals in Pingyao, Lianzhou, Shenyang and Taiwan. Over many trips to Wumeng region, he documented coal miners at work and at leisure as well as the environment in which they lived and the abysmal conditions of the mines themselves. The project that resulted, Wumeng Miners has won him several national photographic awards, and has been widely exhibited in Germany, France and the U.S. A book with the same title was published in 2010.

Hear from the Photographer

Interview from 2015

Q: So…I guess, you have always been saying that the closing of the mines was affecting the community, and you’re saying that’s what’s happening now?

A: 有影响。当地冬季气候寒冷,居民需烧煤取暖,部分小煤窑是村民自给自足生活所需的煤炭,如做饭、烤火。政府关闭之后不允许开采,需另行购买,但他们的经济收入低,负担不起,这对当地老百姓的家庭生活有影响。我曾与煤炭老板交流,如果禁止开采,居民们会转而砍伐树木这另一稀缺资源,将造成更严重的生态环境破坏。

A: The answer must be yes. Because of the cold weather in winter, local people were used to burning coal for heat. Some small-sized coal mines built by the locals provided for their cooking and heating needs. When the mine got closed they had no other way to access coal except buying it, which they could barely afford due to their low income. As I told someone in charge of the coal mines, if mining is banned the locals may turn to cutting down trees, another scarce resource. And this may do greater harm to the environment.

Q: How do local people react when you show your book? Are they surprised at the photos?

A: 当地人还没有机会看到我后来的作品,除了我之前寄回去的合影。当我第二次去煤窑的时候已经找不到他们了。他们不是工人而是种地的农民,人口流动性大,觉得挖煤条件艰苦而且危险所以不做了。

A: I didn’t have a chance to show them my works except the pictures we took together, because when I went back there I couldn’t find them. Local people are not just miners but also farmers. They are moving here and there. Once they realized coal mining is not just tough work but also dangerous, they quit.

Q: What about people in the city unfamiliar with the coal mine? What’s their reaction?

A: 看到展览照片大家都很震惊,不敢相信这样的画面会发生在我们国家,如今社会。包括著名摄影家,北京王文楠(音)先生,观展后感觉“心被撕裂了”。

A: Many citizens are shocked by my exhibition. They just could not believe that kind of scene may occur in our country in today’s society. The famous photographer Wang Wennan from Beijing said after viewing the exhibition that he felt that his “heart was torn apart”.

Q: One of the photos shows a small child in the coal mine, it looks like a very young boy. Can you tell us about that photo?

A: 在拍摄的时候我还没接触过他。当我看到画面的一瞬间,他躺在那儿很打动我(哽咽…)当我准备按下快门的时候,看见他很无助地躺在那儿。我差点不能按下跨门,但还是坚持将他拍了下来。我后来得知他们两兄弟,一个13岁,一个11岁。我的书中还有另一张照片,他们一直很感动我。

A: Not until I finished my work did I get to know the boy. The moment I met him he was lying in front of me, choked. I was so affected I almost couldn’t press the shutter, because he looked so helpless. But I insisted on shooting him. I later learned there were two brothers, one is 13 while the other is 11. There is another photo of them in my book, and it continually touches my heart.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

Cube IV

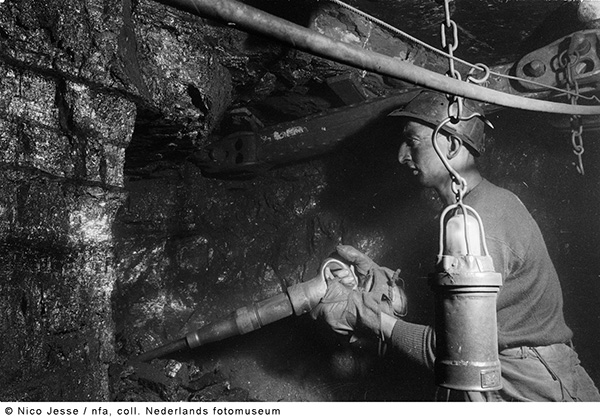

“The essence of [Jesse’s photographs] is the characteristic moment of movement, stripped from everything that does not not directly participate in this movement or to which the movement does not give a certain character.”

–Gerrit Rietveld, Is Photography an Art Form? A Reflection on the Occasion of the Exhibition of Nico Jesse

Nico Jesse was a Dutch photographer born in 1911. For many years he combined his work as a doctor with his passion for photography. In 1956, he decided to end his practice and devote himself exclusively to photography. Six years later, he resumed his former profession, but went on taking photos in his free time. Jesse died in 1976.

Nico Jesse was a Dutch photographer born in 1911. For many years he combined his work as a doctor with his passion for photography. In 1956, he decided to end his practice and devote himself exclusively to photography. Six years later, he resumed his former profession, but went on taking photos in his free time. Jesse died in 1976.

“If you put the focus on the form, the photo dies in beauty.”

–Dolf Kruger, 1987

Swiss-born Dolf Kruger was a Dutch photographer of social problems and causes. Kruger started his career as a freelance photographer before working for the paper De Waarheid. In 1959, he was invited to become a member of the GKf, a professional association of photographers, and in 1961 he won the Silver Camera Award for a photo of the miners’ strike in the Borinage region. After leaving De Waarheid in 1960, he worked as a freelancer for government agencies, publishers, corporations and environmental organizations. In 1983, he settled permanently in Sweden. A monograph of his work was published for a retrospective exhibition in the Amsterdam Historical Museum.

Swiss-born Dolf Kruger was a Dutch photographer of social problems and causes. Kruger started his career as a freelance photographer before working for the paper De Waarheid. In 1959, he was invited to become a member of the GKf, a professional association of photographers, and in 1961 he won the Silver Camera Award for a photo of the miners’ strike in the Borinage region. After leaving De Waarheid in 1960, he worked as a freelancer for government agencies, publishers, corporations and environmental organizations. In 1983, he settled permanently in Sweden. A monograph of his work was published for a retrospective exhibition in the Amsterdam Historical Museum.

Bruce Davidson began taking photographs at the age of ten in Oak Park, Illinois. He became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1958 and created such seminal bodies of work as The Dwarf, Brooklyn Gang, and Freedom Rides. In 1963 the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented his early work in a solo show. His work witnessing the dire social conditions on one block in East Harlem was published in 1970 under the title East 100th Street. In 1980, he captured the vitality of the New York Metro’s underworld that was later published in a book, Subway. His awards include the Lucie Award for Outstanding Achievement in Documentary Photography in 2004 and a Gold Medal Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Arts Club in 2007.

Bruce Davidson began taking photographs at the age of ten in Oak Park, Illinois. He became a full member of Magnum Photos in 1958 and created such seminal bodies of work as The Dwarf, Brooklyn Gang, and Freedom Rides. In 1963 the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented his early work in a solo show. His work witnessing the dire social conditions on one block in East Harlem was published in 1970 under the title East 100th Street. In 1980, he captured the vitality of the New York Metro’s underworld that was later published in a book, Subway. His awards include the Lucie Award for Outstanding Achievement in Documentary Photography in 2004 and a Gold Medal Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Arts Club in 2007.

Landscapes

Polar Ice

Born in Madrid, Spain, Daniel Beltrá is a photographer based in Seattle, Washington. His passion for conservation is evident in images of our environment that are evocatively poignant. In 2011 he received the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Award and the Lucie Award for the International Photographer of the Year – Deeper Perspective for his photography of the Deepwater Horizon Gulf Oil Spill. In 2009 he received the prestigious Prince’s Rainforest Project award granted by Prince Charles. He won the BBVA Foundation award in 2013. Beltrá’s work has been published in many international publications including The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, Le Monde, and El Pais. He is a fellow of the prestigious International League of Conservation Photographers. Website | Instagram

Born in Madrid, Spain, Daniel Beltrá is a photographer based in Seattle, Washington. His passion for conservation is evident in images of our environment that are evocatively poignant. In 2011 he received the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Award and the Lucie Award for the International Photographer of the Year – Deeper Perspective for his photography of the Deepwater Horizon Gulf Oil Spill. In 2009 he received the prestigious Prince’s Rainforest Project award granted by Prince Charles. He won the BBVA Foundation award in 2013. Beltrá’s work has been published in many international publications including The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, Le Monde, and El Pais. He is a fellow of the prestigious International League of Conservation Photographers. Website | Instagram

Hear From The Photographer

Josh Haner is a Staff Photographer and the Senior Editor for Photo Technology at The New York Times. In 2014 he won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for a photo essay documenting the recovery of a Boston Marathon bombing victim. His video on Jeff Bauman’s recovery after the Boston Marathon bombing won first place in the National Press Photographers Association’s Best of Photojournalism and second place in the Pictures of the Year International contest. He was recently selected as “One to Watch” in the September 2012 issue of American Photo magazine. His photography has appeared in numerous publications including Newsweek, Time, Fortune, and Rolling Stone. Website | Instagram | Twitter

Josh Haner is a Staff Photographer and the Senior Editor for Photo Technology at The New York Times. In 2014 he won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for a photo essay documenting the recovery of a Boston Marathon bombing victim. His video on Jeff Bauman’s recovery after the Boston Marathon bombing won first place in the National Press Photographers Association’s Best of Photojournalism and second place in the Pictures of the Year International contest. He was recently selected as “One to Watch” in the September 2012 issue of American Photo magazine. His photography has appeared in numerous publications including Newsweek, Time, Fortune, and Rolling Stone. Website | Instagram | Twitter

Camille Seaman was born in 1969 to a Native American (Shinnecock tribe) father and African American mother. She graduated in 1992 from the State University of New York at Purchase, where she studied photography with Jan Groover and John Cohen. Seaman strongly believes in capturing photographs that articulate that humans are not separate from nature. Her photographs have been published in National Geographic, Italian Geo, German GEO, Time, The New York Times Sunday magazine, Newsweek, Outside, Zeit Wissen, Men’s Journal, Seed, Camera Arts, Issues, PDN, and American Photo, among many others. Her photographs have received many prizes including a National Geographic Award and the Critical Mass Top Monograph Award. She has been a TED Senior Fellow, Stanford Knight Fellow, and a Cinereach Fellow.

Camille Seaman was born in 1969 to a Native American (Shinnecock tribe) father and African American mother. She graduated in 1992 from the State University of New York at Purchase, where she studied photography with Jan Groover and John Cohen. Seaman strongly believes in capturing photographs that articulate that humans are not separate from nature. Her photographs have been published in National Geographic, Italian Geo, German GEO, Time, The New York Times Sunday magazine, Newsweek, Outside, Zeit Wissen, Men’s Journal, Seed, Camera Arts, Issues, PDN, and American Photo, among many others. Her photographs have received many prizes including a National Geographic Award and the Critical Mass Top Monograph Award. She has been a TED Senior Fellow, Stanford Knight Fellow, and a Cinereach Fellow.

Website | Instagram | Twitter | Facebook

Hear From The Photographer

Himalayas

David Breashears is an accomplished mountaineer, photographer, and filmmaker. He is also the founder and Executive Director of GlacierWorks, a non-profit organization that uses art, science, and adventure to raise public awareness about the consequences of climate change in the Greater Himalayan Region. Since 1978 he has combined his skills in climbing and filmmaking to complete more than forty film projects. He co-directed and produced the first IMAX film shot on Mount Everest, and reached the summit of Everest for the fifth time in 2004 when shooting his film Storm Over Everest. Website

David Breashears is an accomplished mountaineer, photographer, and filmmaker. He is also the founder and Executive Director of GlacierWorks, a non-profit organization that uses art, science, and adventure to raise public awareness about the consequences of climate change in the Greater Himalayan Region. Since 1978 he has combined his skills in climbing and filmmaking to complete more than forty film projects. He co-directed and produced the first IMAX film shot on Mount Everest, and reached the summit of Everest for the fifth time in 2004 when shooting his film Storm Over Everest. Website

Hear From The Photographer

“It was a prodigious white fang excrescent from the jaw of the world. We saw Mount Everest not quite sharply defined on account of a slight haze in that direction; this circumstance added a touch of mystery and grandeur; we were satisfied that the highest of the mountains would not disappoint us.”

–George Mallory, diary entry, 1921

Born in 1886, George Mallory was an English mountaineer who took part in the first three British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s. A graduate of Cambridge and a veteran of World War I, Mallory has come to exemplify the dauntless, driven spirit of the first generation of European Everest pioneers. When asked why he wanted to climb Everest, he famously answered “because it’s there.” Mallory and his partner Andrew “Sandy” Irvine disappeared high on Everest during their 1924 Expedition, their second attempt to reach the summit. While Mallory’s body was discovered several hundred feet below the peak in 1999, speculation that he and Irvine could have been the first people to reach the top has never been resolved.

Born in 1886, George Mallory was an English mountaineer who took part in the first three British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s. A graduate of Cambridge and a veteran of World War I, Mallory has come to exemplify the dauntless, driven spirit of the first generation of European Everest pioneers. When asked why he wanted to climb Everest, he famously answered “because it’s there.” Mallory and his partner Andrew “Sandy” Irvine disappeared high on Everest during their 1924 Expedition, their second attempt to reach the summit. While Mallory’s body was discovered several hundred feet below the peak in 1999, speculation that he and Irvine could have been the first people to reach the top has never been resolved.

“I am very frequently asked: ‘What is to be gained when you do reach the summit of Mount Everest?’ From a commercial point of view, nothing….But surely it will be a very great achievement to reach the highest known point on the earth’s surface, and one which should be most appreciated.”

–E. O. Wheeler, 1923

Born in 1890, Edward Oliver Wheeler was a Canadian mountaineer who participated in the first British expedition to Mount Everest, in 1921. A battle-hardened veteran of the First World War, he served as the expedition’s surveyor, introducing the technique of photogrammetric mapping to the British mountaineering elite. While the more famous George Mallory has come to embody the heroic spirit of the early Himalayan pioneers, it was Wheeler who identified the route up Everest with his photographic surveys, thus making it possible for the mountain to finally be summited a generation later.

Born in 1890, Edward Oliver Wheeler was a Canadian mountaineer who participated in the first British expedition to Mount Everest, in 1921. A battle-hardened veteran of the First World War, he served as the expedition’s surveyor, introducing the technique of photogrammetric mapping to the British mountaineering elite. While the more famous George Mallory has come to embody the heroic spirit of the early Himalayan pioneers, it was Wheeler who identified the route up Everest with his photographic surveys, thus making it possible for the mountain to finally be summited a generation later.

“The wish to reproduce faithfully the atmosphere of the panorama even more accurately than it can be seen by the eye or retained by the mind delights the photographer.”

–Vittorio Sella

“The purity of Sella’s interpretations move the spectator to a religious awe.”

–Ansel Adams, Sierra Club Bulletin, 1946

Vittorio Sella was born in the foothills of the Alps in Biella, Italy in 1859. During his long and industrious career as a photographer and mountaineer, Sella took part in many expeditions to the world’s greatest and least explored mountain ranges. Using large-format cameras that had to be carried up the mountain and often developing his plates in portable dark rooms, Sella’s photographs captured alpine scenes with unprecedented vividness and detail.

Vittorio Sella was born in the foothills of the Alps in Biella, Italy in 1859. During his long and industrious career as a photographer and mountaineer, Sella took part in many expeditions to the world’s greatest and least explored mountain ranges. Using large-format cameras that had to be carried up the mountain and often developing his plates in portable dark rooms, Sella’s photographs captured alpine scenes with unprecedented vividness and detail.

Hurricanes

This three-screen projection created by COAL + ICE curator Jeroen de Vries uses found footage of hurricanes from the United States, India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Mexico, and Cape Verde, along with several Caribbean and Central American countries. Most of the footage comes from social media, captured by people who found themselves in the middle of the storms and used their smartphones to document what was happening around them. Additional footage is taken from local news and other sources.

Jeroen de Vries is the designer and co-curator of Coal + Ice. He lives in Amsterdam and Belgrade and works as a freelance designer, curator and teacher. Website

Coal Landscapes

“It is hardly surprising that I was overcome with horror when I noticed that the world in which I was besotted was disappearing.”

–Bernd Becher

“The question ‘is this a work of art or not?’ is not very interesting for us.”

–Hilla Becher

Bernd and Hilla Becher were German photographers whose systematic documentation of their country’s disappearing industrial landscape has been enormously influential for contemporary documentary photography. Inspired by the German interwar New Objectivity movement, the Bechers used rigorous, static composition to photograph their subjects with an almost scientific detachment. The serial photographic “typologies” they created were the signature of what came to be known as the Dusseldorf School, after the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf where the pair taught. Their work influenced a generation of German photographers including Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, and Candida Höfer. Bernd died in 2007 and Hilla in 2015, both in Germany.

Bernd and Hilla Becher were German photographers whose systematic documentation of their country’s disappearing industrial landscape has been enormously influential for contemporary documentary photography. Inspired by the German interwar New Objectivity movement, the Bechers used rigorous, static composition to photograph their subjects with an almost scientific detachment. The serial photographic “typologies” they created were the signature of what came to be known as the Dusseldorf School, after the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf where the pair taught. Their work influenced a generation of German photographers including Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, and Candida Höfer. Bernd died in 2007 and Hilla in 2015, both in Germany.

John Davies was born in County Durham, England and studied photography in Nottingham. After graduating in 1974 he became fascinated by the rural landscape during his visits to the west coast of Ireland. His images of Ireland, Scotland, and England, made between 1976 and 1981, were published in the monograph Mist Mountain Water Wind in 1985. In 1981 he won a Research Fellowship at Sheffield School of Art and in 1995-1996 he was a Senior Research Fellow at the Art School at the University of Wales. Davies was the first photographer to be commissioned by the Museum of London in 2001. His work has been shown at many international venues including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Website | Gallery

John Davies was born in County Durham, England and studied photography in Nottingham. After graduating in 1974 he became fascinated by the rural landscape during his visits to the west coast of Ireland. His images of Ireland, Scotland, and England, made between 1976 and 1981, were published in the monograph Mist Mountain Water Wind in 1985. In 1981 he won a Research Fellowship at Sheffield School of Art and in 1995-1996 he was a Senior Research Fellow at the Art School at the University of Wales. Davies was the first photographer to be commissioned by the Museum of London in 2001. His work has been shown at many international venues including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Website | Gallery

Willem Diepraam was born in Amsterdam in 1944 and began his career in the 1960s as a self-taught photojournalist working for the Dutch newspaper Vrij Nederland. Diepraam’s work demonstrates a sincere concern for the plight of the world’s underprivileged, while his eye never sacrifices elegant form and composition. He has published several books of his own work, including Dutch Caribbean (1975), Sahel (1982), Lima (1991), and Foto’s and Photographs (2000). Diepraam donated part of a 400-print collection of original prints by some of the greatest names in the field to the Rijksmuseum. Website

Willem Diepraam was born in Amsterdam in 1944 and began his career in the 1960s as a self-taught photojournalist working for the Dutch newspaper Vrij Nederland. Diepraam’s work demonstrates a sincere concern for the plight of the world’s underprivileged, while his eye never sacrifices elegant form and composition. He has published several books of his own work, including Dutch Caribbean (1975), Sahel (1982), Lima (1991), and Foto’s and Photographs (2000). Diepraam donated part of a 400-print collection of original prints by some of the greatest names in the field to the Rijksmuseum. Website

Witho Worms is a Dutch artist-photographer. He has a Master’s degree in Anthropology from the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam and studied Audiovisual design and Photography at Utrecht School of the Arts. His background in visual anthropology has led him into an ongoing investigation of the photographic medium and its claim to natural representation and factuality. After photographing the Dutch polders he shifted his attention to slagheaps in the coal mining industries in Western Europe in 2006. In 2013 he started to work on forests in Finland, Sweden, France, and Belgium. His publication La montagne c’est moi was named “The Best Dutch Book Design, 2012” and was short-listed for the Paris Photo-Aperture first Photo Book Award. Stiftung Buchkunst in Germany awarded him the Gold Medal in 2013 for best book design. Website | Instagram

Witho Worms is a Dutch artist-photographer. He has a Master’s degree in Anthropology from the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam and studied Audiovisual design and Photography at Utrecht School of the Arts. His background in visual anthropology has led him into an ongoing investigation of the photographic medium and its claim to natural representation and factuality. After photographing the Dutch polders he shifted his attention to slagheaps in the coal mining industries in Western Europe in 2006. In 2013 he started to work on forests in Finland, Sweden, France, and Belgium. His publication La montagne c’est moi was named “The Best Dutch Book Design, 2012” and was short-listed for the Paris Photo-Aperture first Photo Book Award. Stiftung Buchkunst in Germany awarded him the Gold Medal in 2013 for best book design. Website | Instagram

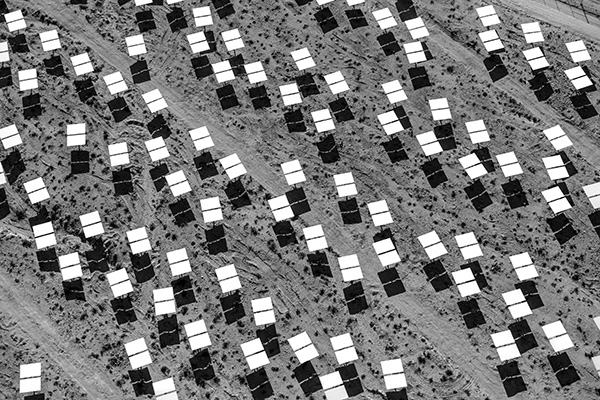

Aerial and location photographer Cameron Davidson calls Northern Virginia home. He creates images from the skies around the globe for advertising campaigns, annual reports, and editorial features. Clients include Vanity Fair, American Express’ Departures, National Geographic, Audubon, Smithsonian, Dominion, and Virginia Tourism. An avid volunteer and board member for the Community Coalition for Haiti (CCH), Davidson has documented CCH aid projects in central and southern Haiti since 1999. Website | Blog | Instagram

Aerial and location photographer Cameron Davidson calls Northern Virginia home. He creates images from the skies around the globe for advertising campaigns, annual reports, and editorial features. Clients include Vanity Fair, American Express’ Departures, National Geographic, Audubon, Smithsonian, Dominion, and Virginia Tourism. An avid volunteer and board member for the Community Coalition for Haiti (CCH), Davidson has documented CCH aid projects in central and southern Haiti since 1999. Website | Blog | Instagram

Hear From the Photographer

Showing the scars from the impact of mountaintop removal coal mining in contrast with the surrounding and untouched landscape was my intent. I felt that showing this desecration of the southern Appalachian Mountains from an aerial perspective would have the greatest impression upon viewers and help them understand the impact on the landscape and watersheds from this type of coal mining.

To be a part of the COAL + ICE exhibition is an honor. This traveling exhibit brings home the message of a focused approach to the consequences of long-term energy consumption and reliance on coal as a source of electrical power.

Anna Filipova is a photojournalist and a researcher based in Paris. She has been working for The New York Times International Edition, The International Herald Tribune, and Reuters News Agency and has been published in CNN, Washington Post, The Telegraph, Dazed & Confused, and The Guardian, amongst others. For the past few years, she has been focusing on the Arctic region, where she explores environmental and social topics in remote and inaccessible areas. She has a MA from the Royal College of Art in London. Most recently, the mayor of Paris and President of C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group selected Filipova as one of the climate heroines representing the city of Paris. Website | Twitter | Instagram

Anna Filipova is a photojournalist and a researcher based in Paris. She has been working for The New York Times International Edition, The International Herald Tribune, and Reuters News Agency and has been published in CNN, Washington Post, The Telegraph, Dazed & Confused, and The Guardian, amongst others. For the past few years, she has been focusing on the Arctic region, where she explores environmental and social topics in remote and inaccessible areas. She has a MA from the Royal College of Art in London. Most recently, the mayor of Paris and President of C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group selected Filipova as one of the climate heroines representing the city of Paris. Website | Twitter | Instagram

Hear From the Photographer

I live in the Arctic, where I cover environmental and science stories. I always try to reveal unseen stories, and to create a sense of wonder. I hope my work will help to strengthen the presence of women in science and environmental photojournalism where previously the feminine perspective has been underrepresented.

Born in 1955 in Henan province’s Baofeng county, Niu has been a freelance photographer since the 1980s and began to photograph coal mines in 1987. He chose coal as his subject because of its centrality in daily life in his home city of Pingdingshan. He has also worked as an official in the Pingdingshan City Bureau of Public Security since 1980, due to the difficulty of making a living as a full-time photographer in China. His major works include Career Behind Bars, Martial Arts, In Dreams, Garden of Hundred Flowers, Small Coal Mines, and Exercises. Niu’s work is in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and has been published in Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Learn more about the Chinese photographers of COAL + ICE: two essays by Marina Svensson

Peter van Agtmael was born in Washington, D.C. in 1981. His work concentrates on America, looking at issues of conflict, identity, power, race, and class. He won the W. Eugene Smith Grant, the ICP Infinity Award for Young Photographer, the Lumix Freelens Award, the Aaron Siskind Grant, and a Magnum Foundation Grant, as well as awards from World Press Photo, American Photography Annual, POYi, The Pulitzer Center, The Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, FOAM, and Photo District News. His book Disco Night Sept 11, on America at war in the post-9/11 era, was named a “Book of the Year” by The New York Times Magazine, Time magazine, Mother Jones, Vogue, American Photo, and Photo Eye. His project Power Down is a portrait of the social and symbolic life of coal in contemporary America. Agtmael joined Magnum Photos in 2008 and became a member in 2013. Website | Instagram | Twitter

Peter van Agtmael was born in Washington, D.C. in 1981. His work concentrates on America, looking at issues of conflict, identity, power, race, and class. He won the W. Eugene Smith Grant, the ICP Infinity Award for Young Photographer, the Lumix Freelens Award, the Aaron Siskind Grant, and a Magnum Foundation Grant, as well as awards from World Press Photo, American Photography Annual, POYi, The Pulitzer Center, The Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, FOAM, and Photo District News. His book Disco Night Sept 11, on America at war in the post-9/11 era, was named a “Book of the Year” by The New York Times Magazine, Time magazine, Mother Jones, Vogue, American Photo, and Photo Eye. His project Power Down is a portrait of the social and symbolic life of coal in contemporary America. Agtmael joined Magnum Photos in 2008 and became a member in 2013. Website | Instagram | Twitter

Born in Madrid, Spain, Daniel Beltrá is a photographer based in Seattle, Washington. His passion for conservation is evident in images of our environment that are evocatively poignant. In 2011 he received the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Award and the Lucie Award for the International Photographer of the Year – Deeper Perspective for his photography of the Deepwater Horizon Gulf Oil Spill. In 2009 he received the prestigious Prince’s Rainforest Project award granted by Prince Charles. He won the BBVA Foundation award in 2013. Beltrá’s work has been published in many international publications including The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, Le Monde, and El Pais. He is a fellow of the prestigious International League of Conservation Photographers. Website | Instagram

Born in Madrid, Spain, Daniel Beltrá is a photographer based in Seattle, Washington. His passion for conservation is evident in images of our environment that are evocatively poignant. In 2011 he received the Wildlife Photographer of the Year Award and the Lucie Award for the International Photographer of the Year – Deeper Perspective for his photography of the Deepwater Horizon Gulf Oil Spill. In 2009 he received the prestigious Prince’s Rainforest Project award granted by Prince Charles. He won the BBVA Foundation award in 2013. Beltrá’s work has been published in many international publications including The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, Le Monde, and El Pais. He is a fellow of the prestigious International League of Conservation Photographers. Website | Instagram

Hear From the Photographer

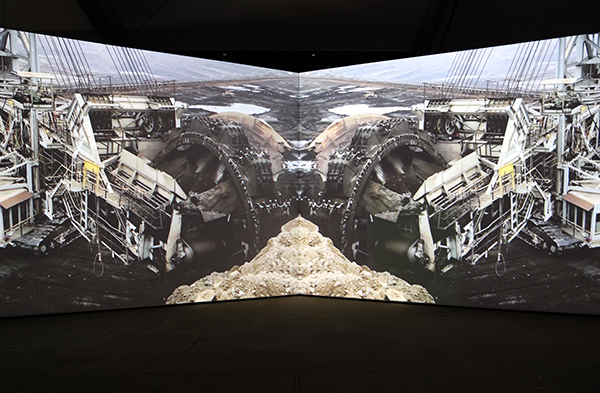

Large Scale Coal Mining

This two-screen projection was created by COAL + ICE curator Jeroen de Vries. It used found footage to depict large-scale coal mining operations including strip mining. It is rare for photographers and filmmakers to have access to large coal mines, especially in China, where half of the material comes from. Most of the footage is a combination of marketing material created by coal companies and clips from Chinese state TV. De Vries’ unique mirrored format turns the stock footage into an artistic presentation that renders earthly images, many of them literally taken underground, otherworldly and strange.

Jeroen de Vries is the designer and co-curator of Coal + Ice. He lives in Amsterdam and Belgrade and works as a freelance designer, curator and teacher. Website

Human Consequences

Cube V

Freelance photographer Noah Berger’s career spans 26 years, shooting for major news outlets including the Associated Press, San Francisco Chronicle, and Agence France-Presse. Berger specializes in documenting wildfires and social unrest. After covering the 2013 Rim Fire outside of Yosemite, he began devoting summers and autumns to documenting California’s fires. He often lives out of his car for days at a time in order to follow the fires as closely as possible. Along with colleagues at the Associated Press, Berger received the 2021 Pulitzer Prize in Breaking News Photography for his coverage of Black Lives Matter protests. He was a 2019 Pulitzer Prize Finalist in Breaking News Photography for his images of California’s deadliest fire season. Website | Instagram | Twitter

Hear From the Photographer

Darcy Padilla is a documentary photographer, an Associate Professor of art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a member photographer of Agence VU’ in Paris. Her work focuses on long-term projects about struggle and its trans-generational effects. Padilla’s honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Open Society Institute Individual Fellowship, an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship, three World Press Photo Awards, and the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography. Her photographs have been published in Granta, Stern, and The New Yorker, among other outlets. She was commissioned for a year to document the 2016 U.S. election for Le Monde. She has had solo exhibitions at Cortona On The Move (Italy), DOCfield Festival (Spain), and Visa pour l’image (France). Padilla’s book Family Love follows a family for 21 years, an intimate story of poverty, AIDS, and social issues. Website | Instagram

Darcy Padilla is a documentary photographer, an Associate Professor of art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a member photographer of Agence VU’ in Paris. Her work focuses on long-term projects about struggle and its trans-generational effects. Padilla’s honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship, an Open Society Institute Individual Fellowship, an Alicia Patterson Foundation Fellowship, three World Press Photo Awards, and the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography. Her photographs have been published in Granta, Stern, and The New Yorker, among other outlets. She was commissioned for a year to document the 2016 U.S. election for Le Monde. She has had solo exhibitions at Cortona On The Move (Italy), DOCfield Festival (Spain), and Visa pour l’image (France). Padilla’s book Family Love follows a family for 21 years, an intimate story of poverty, AIDS, and social issues. Website | Instagram

Hear from the Photographer

One morning I woke up, smelled the smoke, and stared out at the red-orange sky, then brushed away from the window sill the ash that had fallen. The Northern California firestorm had devastated the area and I walked out into the aftermath. I photographed the scarred landscapes and wandered the rubble and tried to make sense of the scattered pieces of people’s lives. These wildfires occurred where houses sit on the edge of nature. The housing crisis is pushing the boundaries of cities. In the United States almost 40% of homes are now at risk.

Darcy Padilla at Agence VU’ Darcy Padilla talks about her series ‘Family Love 1993-2014’, an interview with World Press Photo Foundation Climate Gentrification Could Exacerbate Housing Crisis in South Florida, a photo essay for Sierra Magazine Dana Lixenberg was born in Amsterdam and studied at the London College of Printing and the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. She is known for her understated, intimate portraits, often of underserved communities. Her work is characterized by compositional rigor and the absence of social stereotyping. She uses a large-format camera, which necessitates what she calls a “slow dance” between her and her subjects. Lixenberg’s most extensive project to date is Imperial Courts, 1993-2015, which began in the aftermath of the 1992 Rodney King riots and which documents life in a federal housing project in Watts, Los Angeles over 22 years. Other large-scale projects include Jeffersonville, Indiana (2005), a collection of landscapes and portraits of a small town’s homeless population, and The Last Days of Shishmaref (2008), from which a selection is presented in COAL + ICE. In her editorial work, Lixenberg has also photographed many cultural icons in the United States including Tupac Shakur, Toni Morrison, and Noam Chomsky. Website | Instagram

Dana Lixenberg was born in Amsterdam and studied at the London College of Printing and the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. She is known for her understated, intimate portraits, often of underserved communities. Her work is characterized by compositional rigor and the absence of social stereotyping. She uses a large-format camera, which necessitates what she calls a “slow dance” between her and her subjects. Lixenberg’s most extensive project to date is Imperial Courts, 1993-2015, which began in the aftermath of the 1992 Rodney King riots and which documents life in a federal housing project in Watts, Los Angeles over 22 years. Other large-scale projects include Jeffersonville, Indiana (2005), a collection of landscapes and portraits of a small town’s homeless population, and The Last Days of Shishmaref (2008), from which a selection is presented in COAL + ICE. In her editorial work, Lixenberg has also photographed many cultural icons in the United States including Tupac Shakur, Toni Morrison, and Noam Chomsky. Website | Instagram

Hear From The Photographer

In my projects, I often focus on small, socially and economically isolated communities where I can build relationships with the people and learn about the issues that affect their lives. By spending a certain amount of time in a community, I am exposed to the intimate and often complex relations between the people. Working with a large-format camera on a tripod makes for a slow, organic, collaborative process that gives me time to wait for the moment when my subject’s attitude towards life is revealed in a look or pose. I strive to defy the viewer’s and my own expectations regarding my subjects and the contexts of their lives.

In the winter of 2006, Dutch filmmaker Jan Louter approached me with an offer to join his crew during the filming of a documentary in Shishmaref, a village of 600 Inupiaq people on an island off the coast of Alaska. Shishmaref is disappearing, slowly but surely being swallowed up by the sea. Global warming is melting the island’s protective permafrost layer, and the Chukchi Sea is freezing later in the season, leaving ravaging waves free to batter the island. For all of these reasons, I was curious to experience life in the community and to look beyond the stereotypical and often romanticized images of Eskimo culture presented in different media.